HvMADS1 positively regulates awn development by promoting cell proliferation and further influences spike photosynthesis

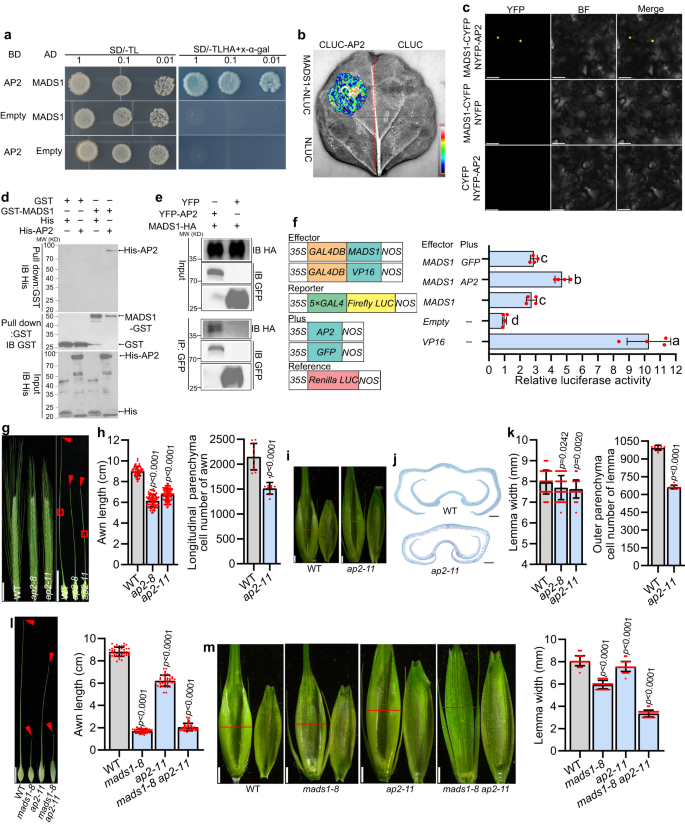

Our previous study demonstrated that HvMADS1 in barley plays an important role in response to high temperature by maintaining a normal, unbranched inflorescence morphology40. Notably, as compared with WT, barley mads1 mutant exhibits shorter awn at ambient temperatures, indicating that HvMADS1 also regulates awn development40; however, the underlying explicit cellular and molecular mechanisms remain unclear.

We generated three knockout lines of HvMADS1 using CRISPR-Cas9 system, namely mads1-3, mads1-5 and mads1-8 in barley cv. Golden Promise (Supplementary Fig. 1a), with different alleles from those reported in previous studies40. All three homozygous mutant plants also exhibited significantly shorter awns than WT plants (Fig. 1a, d), confirming an important role of HvMADS1 in awn development as previously reported40. Cytological analyses on the central parts of the awns revealed that the width and thickness of mads1 awns were also significantly smaller than WT (Fig. 1b, d). The cell width in the transverse section of mads1 awns was slightly smaller than WT, while longitudinal cell length of mads1 was the same as WT (Fig. 1e); remarkably, cell numbers of mads1 awns in both directions were substantially reduced as compared with those in WT (Fig. 1e).

a Images of spike and awn of WT and mads1 knockout lines. Red arrowheads show awn tips; b Transverse (upper) and longitudinal (lower) sections of red boxed regions in (a). Black arrows indicate cells used for cell length measurement and cell number estimation in (e). c Photosynthetic light response curves of intact and de-awned WT and mads1 spikes (n = 3 biological replicates). PFD, photon flux density; Spike Anet, whole-spike net photosynthetic rate. d Statistic data of length, width, and thickness of WT and mads1 awns. e Statistic data of cell length and cell number in both transverse and longitudinal sections of WT and mads1 awns (n = 10 biologically independent samples). f Images of spikelet hulls of WT and mads1. Red lines indicate the position of the cross-section and location of the area used for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) in (g) and (h). g SEM images of the inner surface of WT and mads1 lemmas. h Magnified view of the red boxed lemma area in (g). i Statistic data of lemma width and inner epidermal cell width of WT and mads1 lemmas. j A cross-section of WT and mads1 spikelet hull. k Magnified images of the boxed lemma in (j). Black arrows indicate outer parenchymal cell layers. l Statistic data of the width and number of outer parenchyma cell across WT and mads1 lemmas (n = 10 biologically independent samples). Values are mean ± SD, p values obtained from two-tailed Student’s t-test; Scale bars, 2 cm (a), 100 µm (b, h), 1 mm (f), 0.8 mm (g), 500 µm (j), 50 µm (k). ch chlorenchyma tissue, le lemma, p parenchyma cells, pa palea, pi pistil, T thickness, vb vascular bundle, W width. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

As the mads1 awn was significantly smaller than WT, the corresponding area of chlorenchyma tissue, which contributes to spike photosynthesis and thus grain filling20, was also obviously reduced (Fig. 1b). Consequently, the whole-spike net photosynthetic rate (spike Anet) measured on intact and de-awned WT and mads1 spikes showed that the Anet of mads1 spikes was significantly lower than that of the WT, although slightly higher than that of de-awned mads1 and WT spikes at a photon flux density (PFD) ≥ 250 μmol (photons) m−2 s−1 (Fig. 1c). Most interestingly, the grain weight of de-awned WT was about 6% lower than that of the non-de-awned WT (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Collectively, these results indicated that HvMADS1 controls cell proliferation to positively regulate awn size, which directly affects spike photosynthesis in barley.

HvMADS1 controls lemma width by promoting cell proliferation

MADS1 in rice is well-known for its multiple roles in floral organ identity specification; the osmads1 null mutant displays defective inner floral organs, and an elongated leafy lemma and palea39,41. The spikelets of barley mads1 mutant contained a pair of glumes, a lemma, a palea, and three whorls of internal floral organs, including two lodicules, three stamens, and a carpel, all of which morphologically resembled WT organs (Supplementary Fig. 1c, d, e). However, unlike WT, the mads1 lemma did not completely envelop the palea (Supplementary Fig. 1c, e). Further phenotypic observations found that lemma width, but not palea width or spikelet hull length, is significantly reduced in mads1 spikelets (Fig. 1f, g, i and Supplementary Fig. 1f, g). The width of inner epidermal cell of mads1 was indistinguishable from that of WT (Fig. 1g–i), as were the outer parenchyma cell width (Fig. 1j–l). Cytological analyses revealed that it is the cell number across the lemma width that is reduced in mads1 plants (Fig. 1l). Thus, HvMADS1 also positively regulates lemma width by promoting cell proliferation.

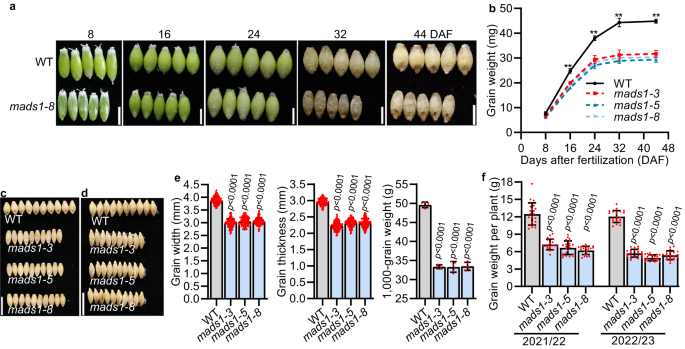

The mads1 mutant produces small grains

In barley and wheat, awns provide photosynthate for developing grains20,21. To examine whether HvMADS1 mediated awn size and lemma size ultimately affects grain size, we compared grain characteristics of WT and mads1 plants along grain development process. The obvious differences in grain size and weight were observed from 16 days after fertilization (DAF), in which the weight of mads1 grain was significantly lower than those of WT (Fig. 2a, b). Although there was a slight increase in length, significant decreases in both width and thickness of mads1 grain were observed as compared to WT (Fig. 2c–e and Supplementary Fig. 2a, b), which was consistent with observed narrower lemma in mads1 (Fig. 1f, i). To rule out the effect of carpel size on grain size, we also compared carpels size between WT and mads1 mutant, and found that the carpel size of the mutant was not significantly smaller than that of the WT (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). In addition, to rule out the effect of endosperm on grain size we crossed mads1 (♀) with WT (♂), and found that grain size of all F2 progenies is similar to that of WT (Supplementary Fig. 3c, d). These results implied that the spikelet hull in barley is an important factor limiting grain size as it is in rice, as lemma width can directly affect the grain width and thickness (Fig. 2c–e).

Images (a) and staistic data of weight (b) of WT and mads1 grains at different developmental stage (n = 3 biological replicates). Images (c, d) and statistic data (e) of the width, thickness and 1,000-grain weight of mature WT and mads1 grains (n = 150 individual grains for grain size and n = 5 biological replicates for grain weight). f Staistic data of grain weight per plant of WT and mads1 grown in the paddy field in Shanghai for two consecutive years (2021–22 and 2022–23). Values are mean ± SD, two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to generate the p values; **p < 0.01; Scale bars, 0.5 cm (a), 1 cm (c, d). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The weight of mads1 grains was about 33 % lower than that of WT grain (Fig. 2e). This agronomically important result was confirmed in two-year field trials (Supplementary Fig. 2c). It is worth noting that although the spike length, spikelet number per spike and plant of mads1 were not significantly reduced compared with those of the WT (Supplementary Fig. 2d, e, f), grain numbers per spike and grain numbers per plant of mads1 were smaller than those of WT (Supplementary Fig. 2g, h). This was mainly due to much lower seed setting rate of mads1, which was 32-39% lower than that of WT (Supplementary Fig. 2i). Consequently, the overall grain yield (weight) per plant in mads1 was decreased 42–59% as compared with that of WT (Fig. 2f), suggesting that HvMADS1 is important for sustaining barley grain yield.

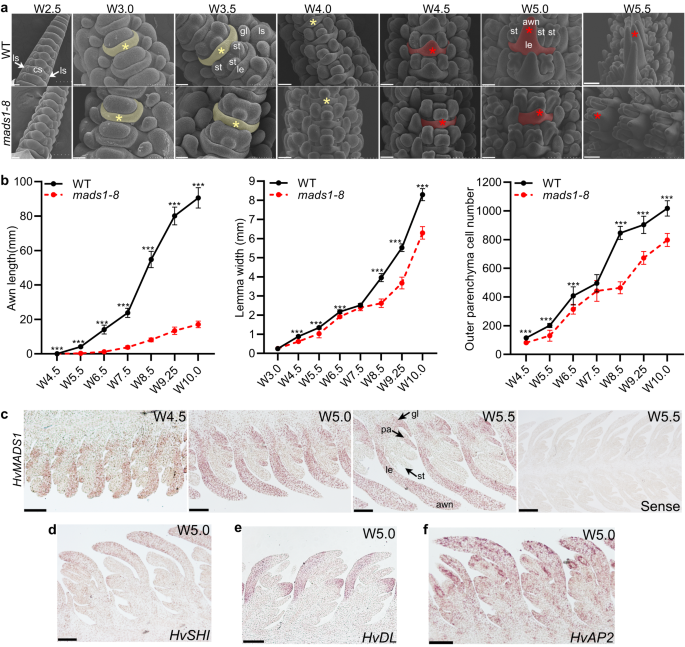

HvMADS1 expression promotes awn development and lemma transverse growth

To determine the specific stages at which HvMADS1 affects awn and lemma differentiation and development, we compared WT and mads1 spikelet development using SEM at different Waddington stages (W2.5–W5.5)42, including W3.0 and W4.5 when lemma and awn primordia initiate, respectively. At stage W3.0, lemma primordia initiated normally in both WT and mads1 (Fig. 3a). During stages W4.5–W5.5, awn primordia emerged at the lemma apex similarly in both WT and mads1, which, however, elongated rapidly in WT but slowly in mads1 (Fig. 3a). Afterwards, awn length, lemma width, and the cell number of the lemma increased rapidly in WT but slower in mads1, especially after stage W7.5 (Fig. 3b).

a SEM images of WT and mads1 spikelets at different developmental stages (W2.5–W5.5). Yellow shading and star indicate lemma; red shading and star indicate lemma and awn. Scale bars, 50 µm (W3.0, W3.5), 80 µm (W2.5, W4.0, W4.5, W5.0), 160 µm (W5.5). b Dynamic changes of awn length, lemma width, and cell number across the lemma along the process of inflorescence development. The width and cell number of the lemma were obtained by analyzing lemma sections (n = 10 individual lemma samples for lemma width at stages W6.5-W10.0). c–f Results of RNA in situ hybridization of HvMADS1 (c), SHORT INTERNODES (HvSHI, d), DROOPING LEAF (HvDL, e) and APETALA2 (HvAP2, f) in longitudinal sections of developing WT inflorescences. Scale bars, 100 µm (except for W5.5 sense probe panel bar, 250 µm). (a, c–f) The representative results from three independent replicates were presented. Values are mean ± SD, asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (two-tailed Student’s t-tests; ***P < 0.001). cs central spikelet, gl glume, le lemma, ls lateral spikelet, pa palea, pi pistil, st stamen. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To confirm the correlation between HvMADS1 expression and observed phenotype, we performed gene expression analysis. Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) results revealed that HvMADS1 is relatively high expressed in developing inflorescences at stages W5.0–W9.5, the period of floral organ development including rapid growth of the lemma and awn (Supplementary Fig. 4a). RNA in situ hybridization revealed that HvMADS1 transcripts are abundant in the awn and lemma primordia at stages W4.5, W5.0, and W5.5 (Fig. 3c). Together, these results suggest that specific expression of HvMADS1 induces rapid cell division/proliferation in the lemma and awn.

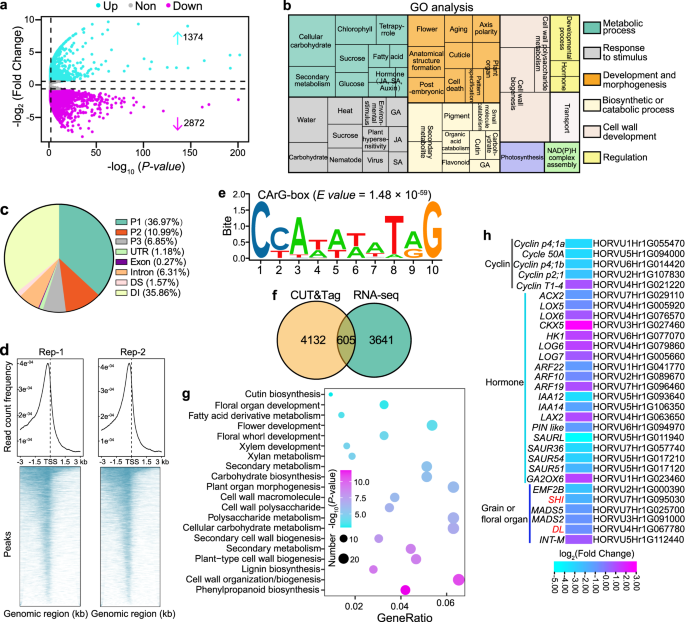

HvMADS1 regulates hormone- and cell cycle–related genes

To better investigate biological processes influenced by HvMADS1 mutations, we performed transcriptomic (RNA-seq) analysis of WT and mads1 lemma and awn at stage W7.5 before the awn longitudinal growth and lemma transverse growth started to differ dramatically (Fig. 3b). Differential gene expression analysis detected 1,374 up-regulated and 2,872 down-regulated genes in mads1 relative to WT (Fig. 4a). Gene ontology (GO) term analysis revealed that differentially expressed genes (DEGs) are enriched for biological processes including flower morphogenesis, plant organ development, hormone metabolism, response processes, and cell wall development (Fig. 4b). Specifically, some of these DEGs are annotated to be involved in auxin, gibberellin, jasmonic acid, and cytokinin metabolic and signaling processes (Supplementary Fig. 5a), which is consistent with previous reports that there are many hormone-related genes downstream of MADS1, and that these four hormone families are involved in barley and/or rice spikelet development40,43,44,45. Additionally, expression of cell cycle-related genes was generally down-regulated in mads1 lemmas and awns, which was further confirmed by RT-qPCR (Supplementary Fig. 5b, c), consisting with the finding that HvMADS1 promotes cell proliferation in these tissues (Fig. 1).

a The Volcano plot of DEGs in lemma and awns between mads1 and WT. Blue and purple points represent up- and down-regulated genes, respectively; Gray points represent insignificantly changed genes. Cut-off value was set to false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05, absolute fold change ≥ 1.5, FDR was adjusted by Benjamini–Hochberg correction. b Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of DEGs in (a). c CUT&Tag analysis of MADS1-binding regions in genomic regions of direct target genes: P1, 0–1 kb upstream of start codon; P2, 1–2 kb upstream of start codon; P3, 2–3 kb upstream of start codon; DS, 1–300 bp downstream of stop codon; DI, >300 bp downstream of stop codon. d The distribution of CUT&Tag peaks around transcriptional start sites (TSS). e Preferred CArG-box sequence for HvMADS1 binding. f The Venn diagram showing overlapped genes jointly identified by RNA-seq and CUT&Tag analyses. g GO enrichment analysis of 605 putative direct target genes identified from (f), p values were calculated by the Fisher method. h A heat-map showing expression patterns of putative HvMADS1 direct target genes in lemmas and awns between mads1 and WT.

To further unearth direct targets of HvMADS1 regulation, we performed Cleavage Under Targets and Tagmentation (CUT&Tag) assays using stage W7.5 lemma and awn from an existing HvMADS1-eGFP transgenic line40. We identified 4,737 predicted direct target genes (Supplementary Data 1); approximately half of HvMADS1 binding sites for these genes were located in the 2 kb promoter region upstream of the start codon (Fig. 4c), in agreement with the idea that HvMADS1 acts as a transcription factor. The highest frequency of binding occurred around the transcriptional start site (TSS; Fig. 4d), while one of the most enriched sequences for the in vivo HvMADS1-binding motif (E value = 1.48 × 10−59) was a cis-element CArG-box (Fig. 4e).

Intersection of RNA-seq and CUT&Tag data identified 605 genes as the most likely direct targets of HvMADS1 (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Data 2). Further GO analysis revealed that these targets are also significantly enriched in floral organ development, plant organ morphogenesis, and cell wall-related processes (Fig. 4g). Notably, the heatmap and genome browser view showed that HvSHI and HvDL expression is significantly suppressed in mads1 lemmas and awns (Figs. 4h, 5a, j and Supplementary Data 3). HvSHI is considered as a strong candidate for the short awn 2 (Lks2) trait involved in barley awn elongation22, whereas homologs of HvDL is involved in awn development in wheat and rice30,35. Our combined methods also revealed several other direct candidate targets of HvMADS1 that are involved in floral organ development, cell cycle, and auxin response processes (Fig. 4h and Supplementary Fig. 5d).

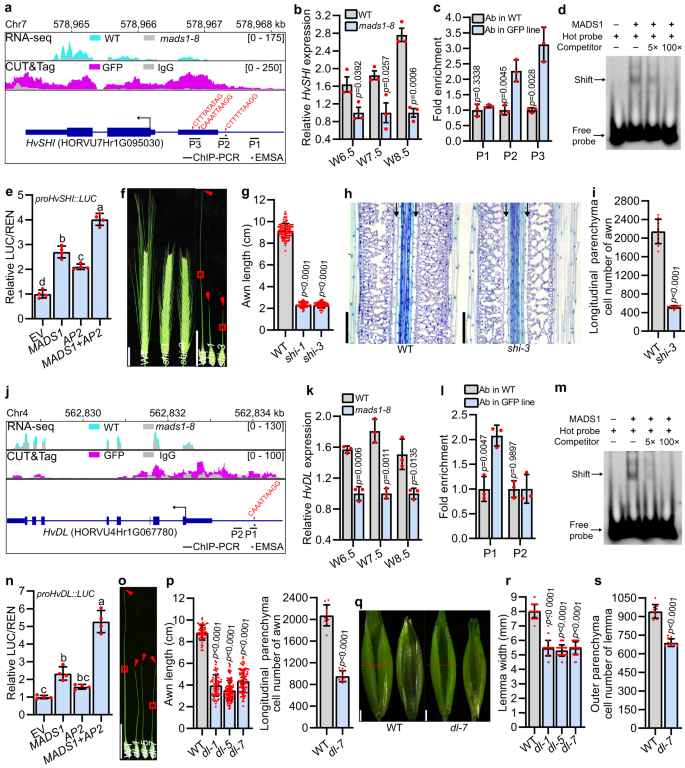

a, j Genome browser view of RNA-seq and CUT&Tag profiles and the schematic diagram of promoter fragments of HvSHI (a) and HvDL (j) for ChIP-PCR and EMSA assay in (c, d, l, m). Expression of HvSHI (b) and HvDL (k) in developing lemma and awn of WT and mads1. c, l Binding of HvMADS1 to the HvSHI (c) and HvDL (l) promoters in vivo as revealed by ChIP-PCR. Binding of MADS1 to probes from the HvSHI (d) and HvDL (m) promoters harboring a CArG-box (EMSA), a representative result from three replicates was presented. Transactivation activity assay of HvMADS1 and HvMADS1-HvAP2 interaction on HvSHI (e) and HvDL (n). Different letters represent significant differences (p < 0.05) determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Images of shi (f) and dl (o) awns. Longitudinal sections of boxed regions in (o) are shown in Supplementary Fig. 7c. g Statistic data of WT and shi awns. h Longitudinal sections in the boxed regions of (f). Black arrows indicate cells used to measure cell length for cell number estimation in (i). i, Statistic data of longitudinal parenchyma cell number in WT and shi awns. p Statistic data of the length and cell number of WT and dl awns. q Images of spikelet hulls of WT and dl. Red lines indicate the position of the cross-section used in (r, s). Statistic data of the width (r) and number of the outer parenchyma cell (s) in the lemma of WT and dl. Values are mean ± SD, p values shown are from two-tailed Student’s t-test; n = 3 and 4 biological replicates for (b, c, k, l) and (e, n), respectively. Scale bars, 2 cm (f, o), 1 mm (q), 100 µm (h). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

HvMADS1 could regulate awn and lemma development through direct regulation of potential targets HvSHI and HvDL

Expression analysis revealed that both HvSHI and HvDL are expressed in the developing inflorescence of WT (Supplementary Figs. 6a, 7a), and that their expression levels are significantly downregulated in mads1 lemma and awn at stages W6.5, W7.5, and W8.5 (Fig. 5b, k). In situ hybridization confirmed the specific expression of HvSHI in awn (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 4b) and HvDL in both lemma and awn (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 4c), suggesting that these two genes likely function in awn and/or lemma development. ChIP-qPCR assays further corroborated that HvMADS1 directly binds in vivo to HvSHI and HvDL promoter fragments containing a CArG-box motif (Fig. 5c, l), which was subsequently verified in vitro by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA; Fig. 5d, m). Dual-luciferase (LUC) assays in barley protoplasts showed that HvMADS1 can transiently activate the expression of HvSHI and HvDL (Fig. 5e, n), confirming that HvMADS1 can directly bind to promoters of HvSHI and HvDL to activate their transcription.

To confirm whether HvSHI and HvDL affect barley awn and lemma development, we created HvSHI mutants (named shi-1 and shi-3; Supplementary Fig. 6b) and HvDL mutants (dl-1, dl-5 and dl-7; Supplementary Fig. 7b) via CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing. As in mads1 mutants, awns of the shi and dl mutants were significantly shorter than that of WT, primarily due to a reduction in cell number rather than in cell size (Fig. 5f–i, o, p, and Supplementary Fig. 6c, 7c, d). Correspondingly, the 1,000-grain weight of shi mutant was significantly smaller than that of WT (Supplementary Fig. 6d).

Notably, our observations showed that the dl mutant exhibits a significantly narrower lemma (Fig. 5q, r) but similar spikelet hull length and palea width, as compared with WT (Supplementary Fig. 7e, f). As dl mutants were unable to set seeds due to defective pistils with ectopic carpel-like organs (Supplementary Fig. 7g), the grain size of dl mutants could not be obtained. Microscopic observation of lemma cross-sections further revealed significantly reduced cell number in dl, which mimicked the defect in mads1 (Fig. 5s and Supplementary Fig. 7h). SEM results confirmed that, similar to mads1, it is not the initiation of dl lemma but the growth of shi and dl awns is slowed down as compared to that in WT (Supplementary Fig. 8). Correspondingly, expression levels of a number of cell cycle genes, whose expression was significantly decreased in mads1, were also remarkably down-regulated in shi and dl mutants (Supplementary Fig. 6e, 7i). These results implied that the direct regulation of potential targets HvSHI and HvDL by HvMADS1 could contribute to HvMADS1-dependent regulation of awn and/or lemma development through controlling cell proliferation.

Interaction of HvMADS1 with HvAP2

SEP proteins, to which MADS1 belongs, often form higher-order complexes with other ABCDE proteins to regulate floral organ development46,47. Our yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assay confirmed above mentioned idea and found that HvMADS1 interacts with other A-, B-, C-, D-, E-class, and AGL6 subfamily homeotic proteins except HvMADS4 and HvMADS14 (Supplementary Fig. 9). Most interestingly, HvMADS1 interacted with HvAP2 in yeast cells (Fig. 6a). Considering the fact that HvAP2 was reported to regulate awn development37, we speculate that HvMADS1 and HvAP2 might function together in barley awn development. The interaction of the HvAP2 with HvMADS1 was subsequently confirmed by split firefly luciferase complementation (SFLC) assays and bimolecular florescence complementation (BiFC) assays in tobacco epidermal cells (Fig. 6b, c), and further validated by in vitro pull down and in vivo Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assays (Fig. 6d, e). Further investigations showed that the intervening (I) and keratin-like (K) domain of HvMADS1 are required for physical interaction with HvAP2 (Supplementary Fig. 10a), and that HvAP2 interacts with HvMADS1 likely through its C- and N-terminal domain (Supplementary Fig. 10b). A transient transcriptional activity assay demonstrated that the interaction of HvMADS1 with HvAP2 significantly enhances transcriptional activity of HvMADS1 (Fig. 6f). Additional RT-qPCR and in situ hybridization revealed that HvAP2 is ubiquitously expressed in developing floral organs, including in the awn and lemma during inflorescence development (Fig. 3f, Supplementary Figs. 4d and 11a), which overlapped with that of HvMADS1.

a–e Interaction between MADS1 and HvAP2. Yeast two-hybrid assay (a): AD, GAL4 activation domain; BD, GAL4 DNA-binding domain; SD/-TL and SD/-TLHA, synthetic defined medium without Trp and Leu or without Trp, Leu, His and Ade, respectively. Split firefly luciferase complementation (SFLC) assay in tobacco leaves (b): Scale bar represents luminescence intensity. Bimolecular florescence complementation (BiFC) assay in tobacco epidermal cells (c). In vitro pull-down assay (d): GST-MADS1 was incubated with His-AP2, pulled down using anti-GST beads, and detected by anti-His immunoblotting. IB, Immunoblot. In vivo Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay in tobacco leaves (e): GFP beads were used for immunoprecipitation (IP). f Effects of HvMADS1–HvAP2 interaction on HvMADS1-induced transcriptional activation (n = 4 biological replicates); Different letters indicate significant differences according to one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (p < 0.05). Images (g) and statistic data of length, and cell number (h) of WT and ap2 awns. Longitudinal sections of boxed regions in (g) are shown in Supplementary Fig. 11c. i Images of WT and ap2 spikelet hulls. Red lines indicate the position of the cross-section used in (j, k). j Cross-sections of WT and ap2 spikelet hulls. k Statistic data of the width and outer parenchyma cell number of WT and ap2 lemmas. Statistic data of awn length (l), images and statistic data of lemma width (m) of WT, mads1-8, ap2-11 and mads1-8 ap2-11 double mutant. Values are mean ± SD, p values shown are from two-tailed Student’s t-test; For (a, b, c, d, e), a representative result is shown from three independent replicates. Scale bars, 50 μm (c), 2 cm (g), 1 cm (l), 1 mm (i, m), and 250 µm (j). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further explore the functions of HvAP2, we generated ap2 knockout mutants (ap2-8 and ap2-11; Supplementary Fig. 11b). Phenotypic analysis confirmed that HvAP2 also promotes awn growth mainly by affecting cell number (Fig. 6g, h, and Supplementary Fig. 8, 11c, d), and that the ap2 lemma is also slightly narrower due to the reduced cell number (Fig. 6i–k). The width and thickness of ap2 grain were significantly narrower than WT (Supplementary Fig. 11g, h). The observed phenotypes of awn length and grain size of ap2 mutants are consistent with previous reports37. To further test the genetic relationship between MADS1 and AP2 with respect to awn length and lemma width, we created mads1-8 ap2-11 double mutant by crossing mads1-8 with ap2-11. Phenotypic similarities of the degree of awn length shortening between mads1-8 and mads1-8 ap2-11 (Fig. 6l) indicated that HvMADS1 is genetically epistatic to HvAP2 in the control of awn growth. The lemma width of double mutant was significantly reduced, much narrower than that of mads1-8, ap2-11 and WT (Fig. 6m). Taken together, these findings indicate that HvMADS1 and HvAP2 synergistically regulate the awn and lemma development. Expression analysis found that expression levels of HvSHI and HvDL, as well as several cell cycle genes that are downregulated in mads1, are also significantly reduced in ap2 mutants (Supplementary Fig. 11i). Dual-LUC assays demonstrated that HvSHI and HvDL promoter activation is much significantly enhanced when HvAP2 and HvMADS1 are co-transformed than HvMADS1 alone (Fig. 5e, n). Thus, HvMADS1 and HvAP2 may form a complex and regulate the common target genes HvSHI and HvDL to control awn size and/or lemma transverse growth.

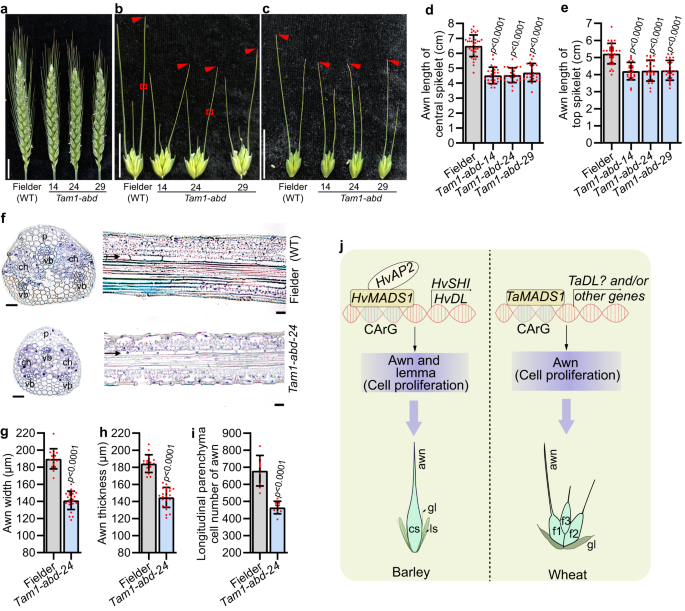

The function of bread wheat MADS1 in regulating awn size

There are three wheat homologs of HvMADS1, namely TaMADS1-A (TraesCS4A01G058900), TaMADS1-B (TraesCS4B01G245700), and TaMADS1-D (TraesCS4D01G243700; Supplementary Fig. 12a). To investigate whether TaMADS1 is involved in wheat awn and lemma development, we generated a triple recessive mutant of TaMADS1 (Tam1-abd) in hexaploid bread wheat cultivar Fielder by CRISPR-Cas9 (Supplementary Fig. 12b). Interestingly, the awns of both central and top spikelets in Tam1-abd were significantly smaller compared to those of WT (Fig. 7a–e, g, h). Further histological experiments demonstrated that the number of longitudinal parenchyma cell of the Tam1-abd awn was reduced by 31.8 % compared to that of WT, while the cell length was not significantly changed (Fig. 7f, i and Supplementary Fig. 12c). Thus, consistent with barley results, reduction in cell number due to the Tam1-abd mutation likely resulted in shorter awns in wheat mutant. Notably, Tam1-abd did not show any phenotypes in lemma and other floral organs, due likely to the functional redundancy since TaMADS1 has duplicated in wheat (Supplementary Fig. 12a).

a Images of Fielder (WT) and three independent Tam1-abd mutant spikes at heading day. b, c Images of WT and Tam1-abd awns from the central (b) and top (c) spikelets. Statistic data of awn lengths from the central (d) and top (e) spikelets. f Sections from the boxed regions of (b) showing the size and number of cells in WT and Tam1-abd awns. g–i Statistic data of width (g), thickness (h), and longitudinal parenchyma cell number (i) of WT and Tam1-abd awn. j A proposed model for MADS1-mediated awn and lemma development. In barley, HvMADS1 and HvAP2 form a complex that jointly activates potential downstream genes HvSHI and HvDL, further influencing cell proliferation and ultimately controlling the elongation of the awn and lemma transverse growth. In wheat, TaMADS1 can also control awn elongation by influencing cell proliferation. Values are mean ± SD, p values obtained from two-tailed Student’s t-test; Scale bars, 2 cm (a, b, c), and 25 µm (f). ch chlorenchyma tissue, f1–3 flower 1–3, cs central spikelet, gl glume, p parenchyma cells, ls lateral spikelet, vb vascular bundle. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.